No Adult Left Behind: Adult Learning Theories for Training Officers

May 2, 2023

By Rachel Buczynski

When we think of the science of how humans learn, we often think of children (i.e., pedagogy). However, there are learning theories unique to adults: how people learn in formal and informal ways once they are over 18. While there are specific requirements for K-12 teachers, many training officers (in all industries) find themselves in the role with little to no background knowledge of andragogy (the science of adult learning). Understanding more about andragogy can help you further build your skillset as a trainer and reinforce techniques you’re already using.

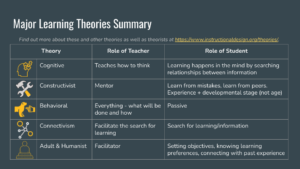

There are many well-researched theories of adult learning that provide key takeaways that can be combined into practice. First, let’s review a few of the leading theories, and then we’ll look at what that means for your training program. (Please note, the explanations below are a very simplistic summary for informational purposes; for more information and links to the original research, visit www.instructionaldesign.org/theories.)

Cognitive: Information is actively processed in the mind and learning happens by finding relationships between what you already know and new information. The trainer’s role is to teach the learner how to learn. Think of a jigsaw puzzle – the learner needs to understand how to connect the pieces to form a whole picture.

Cognitive: Information is actively processed in the mind and learning happens by finding relationships between what you already know and new information. The trainer’s role is to teach the learner how to learn. Think of a jigsaw puzzle – the learner needs to understand how to connect the pieces to form a whole picture.

- Application: When introducing a new tool at the department, ask participants to think and share about how the new tool is similar to and different from other tools they’ve used before moving into the training lesson on how to use the new tool. Showing them how to think through this process will help them when they encounter an unfamiliar tool in the future.

Constructivist: People construct knowledge, rather than receiving it. In other words, they build upon what they know to create new ideas. The instructor serves as a mentor and guide rather than providing direct instruction. Gaining knowledge comes from trying things, making mistakes, and learning from peers.

Constructivist: People construct knowledge, rather than receiving it. In other words, they build upon what they know to create new ideas. The instructor serves as a mentor and guide rather than providing direct instruction. Gaining knowledge comes from trying things, making mistakes, and learning from peers.

- Application: Give your training participants the new tool. Encourage them to work together to determine how they would use it. Provide corrections and guidance when attempts are unsuccessful. After they’ve successfully figured out how to operate the tool, provide written guidance incorporating their lessons learned.

Behavioral: This is classic stimulus and response – i.e., Pavlov’s dogs. It is completely trainer-led; the trainer tells learners what will be done and how it will be done, and the result should happen on demand. The response to this can be positive or negative.

Behavioral: This is classic stimulus and response – i.e., Pavlov’s dogs. It is completely trainer-led; the trainer tells learners what will be done and how it will be done, and the result should happen on demand. The response to this can be positive or negative.

- Application: What happens when you hear the tone drop? You automatically act. You’ve been behaviorally conditioned to do what needs to be done based on a signal. This can be incredibly important for safety and quick action in an emergency. However, adults tend to reject behavioral training in other training situations – they prefer to know why they are doing something and connect it with their experience. This is the difference between “because I said so” and giving the “why.”

Connectivism: This is a newer theory focused on the role of technology in learning. The limitless resources that anyone can now access online provides opportunities for independent learning. The trainer’s role here is to teach how to find and access reliable resources.

Connectivism: This is a newer theory focused on the role of technology in learning. The limitless resources that anyone can now access online provides opportunities for independent learning. The trainer’s role here is to teach how to find and access reliable resources.

- Application: Show your department members where to find department-approved online training and resources, including tutorials, videos, on-demand trainings, webinars, and product usage guides. Encourage them to explore these resources and share out new ideas with each other.

Humanist: This is person-centered learning; the learner has an active role in deciding what they should learn. The teacher then acts as a facilitator to gaining the requested knowledge. The trainer involves learners in setting objectives and considers their motivation for learning and past experiences when developing training.

Humanist: This is person-centered learning; the learner has an active role in deciding what they should learn. The teacher then acts as a facilitator to gaining the requested knowledge. The trainer involves learners in setting objectives and considers their motivation for learning and past experiences when developing training.

- Application: Invite department members to provide ideas on training night topics and incorporate their expertise by inviting them to present on topics when appropriate.

So, how do you put this all together to benefit your training program? Each of these theories has strengths and weaknesses, and some work better in some situations than others. Here are key takeaways to consider:

- Connect to their experience. Most theories of adult learning emphasize the importance of connecting new information to lived experience. Learn about your members’ past experiences and use that to connect with new information.

- Include them in the conversation. Motivation is also a key part of adult learning. Sure, you can require a certain number of training hours per month, but your participants will be more engaged and gain more knowledge if you tie training to their goals and motivation for learning.

- Give them the chance to figure it out. While this may not work for some training for safety reasons, when appropriate, let your learners explore an idea, topic, or tool on their own before providing a lesson or presentation. They’ll retain knowledge better and build their teamwork skills by working through a challenge together.

- Use the group knowledge to your advantage. Volunteer first responders come from all backgrounds and levels of experience – include them in your training plans. Maybe an officer can conduct a leadership training, someone who works in marketing can discuss public image, and a tech-savvy member can show the members how to use social media for community outreach.

- Provide numerous and diverse learning opportunities. Training doesn’t just happen on training night! Show members where to find training information and resources and encourage them to share new sources they find as well. Incorporate written instruction, hands-on and tactical training, videos, and more.

Rachel Buczynski is passionate about creating impactful, accessible lifelong learning opportunities for everyone. As the National Volunteer Fire Council’s (NVFC) chief of training and education, she oversees the NVFC’s in-person and virtual training and educational activities, including conferences, webinars, and the Virtual Classroom. Rachel brings to this role over 15 years’ experience working with local, national, and international nonprofits on educational events and program development, including the NVFC and other fire service organizations. She holds a master’s degree in adult education and human resource development from James Madison University.

Rachel Buczynski is passionate about creating impactful, accessible lifelong learning opportunities for everyone. As the National Volunteer Fire Council’s (NVFC) chief of training and education, she oversees the NVFC’s in-person and virtual training and educational activities, including conferences, webinars, and the Virtual Classroom. Rachel brings to this role over 15 years’ experience working with local, national, and international nonprofits on educational events and program development, including the NVFC and other fire service organizations. She holds a master’s degree in adult education and human resource development from James Madison University.